TL;DR: We present Medmarks v0.1, the first release of our new evaluation suite for assessing the medical capabilities of LLMs. It comes with 2 subsets, a verifiable set of tasks and an open-ended set of tasks. This suite is the largest completely open-source automated evaluation suite for medical capabilities, with a total of 20 benchmarks. It covers tasks like answering patient questions to detecting errors in clinical notes. So far we’ve evaluated 46 models with 56 configurations. The best performing models on our benchmark suite were GPT-5.1, GPT-5.2, and Qwen3 235B-A22B Thinking. We will continue to update our leaderboard with new models and tasks.

Introduction

There has been a lot of interest recently in medical applications for large language models (LLMs), with tasks spanning hospital administrative workflows, clinical decision support, patient-facing chat bots, and more. Doctors are already using LLMs to help diagnose patients, and specialized tools like OpenEvidence are seeing huge popularity.

For these reasons, a proper benchmarking harness is essential. We need to be able to accurately track the medical capabilities of frontier LLMs and understand their limitations in order to ensure safe deployment of current LLMs and to improve the future generations of LLMs for medical use-cases.

In a formidable effort led by Sophont and our MedARC research community, with the support of Prime Intellect, we’ve been building exactly this over the course of the last three months.

Today we present v0.1 of Medmarks, a new evaluation suite for assessing the medical capabilities of LLMs. This suite is the largest completely open-source automated evaluation suite for medical capabilities, with a total of 20 benchmarks. So far we’ve evaluated 46 models with 56 configurations. This is a live leaderboard, meaning we will continually update it with new models and new datasets.

We developed two subsets of benchmarks: Medmarks-Verifiable (multiple-choice question answering and other verifiable tasks) and Medmarks-OE (open-ended, non-verifiable tasks evaluated using LLM-as-a-Judge).

We evaluated both proprietary model APIs from frontier labs and open-source models running locally, ranking models based on a weighted mean win rate. A few overall takeaways are that GPT-5.1, GPT-5.2, and Qwen3 235B-A22B Thinking were the best performing models on our benchmark. Also, we observed that medically tuned LLMs like Baichuan-M2 outperformed much larger generalist models like GLM-4.5 Air, highlighting the potential for medical-specific post-training.

We release the benchmarks on the Prime Intellect Hub here. Our code for running these benchmarks is available here.

| Model | Weighted Mean Win Rate |

|---|---|

| GPT 5.1 (medium) | 0.6561 |

| Grok 4 | 0.6557 |

| GPT 5.2 (medium) | 0.6489 |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 0.632 |

| Qwen3 235B-A22B Thinking 2507 | 0.6219 |

| Qwen3 Next 80B-A3B Thinking 2507 | 0.6078 |

| gpt-oss 120b (high) | 0.5981 |

| gpt-oss 120b (medium) | 0.589 |

| Qwen3 Next 80B-A3B Instruct 2507 | 0.5817 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 FP8 | 0.5718 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 AWQ 8bit | 0.5713 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 | 0.5704 |

| INTELLECT-3 | 0.5647 |

| gpt-oss 120b (low) | 0.5623 |

| Baichuan M2 32B | 0.5596 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 AWQ 4bit | 0.5585 |

| GLM-4.5 Air | 0.5515 |

| Qwen3 14B (Thinking) | 0.5456 |

| Llama 3 70B Instruct | 0.5444 |

| MiniMax M2 | 0.5433 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Instruct 2507 | 0.5401 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Instruct 2507 AWQ 8bit | 0.5397 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Instruct 2507 FP8 | 0.5385 |

| gpt-oss 20b (high) | 0.538 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Instruct 2507 AWQ 4bit | 0.5296 |

| gpt-oss 20b (medium) | 0.5176 |

| Olmo 3.1 32B Think | 0.5111 |

| MedGemma 27B | 0.5069 |

| Qwen3 8B (Thinking) | 0.5043 |

| Nemotron Nano 12B V2 | 0.5021 |

| Olmo 3 32B Think | 0.5008 |

| Magistral Small | 0.4982 |

| Qwen3 4B Thinking 2507 | 0.4883 |

| Ministral 3 14B Reason 2512 | 0.4852 |

| Ministral 3 14B Instruct 2512 | 0.4844 |

| gpt-oss 20b (low) | 0.4717 |

| Hermes 4 70B | 0.4704 |

| Trinity Mini | 0.4684 |

| Ministral 3 8B Instruct 2512 | 0.4682 |

| Phi 4 reasoning | 0.4579 |

| Hermes 4 14B | 0.4579 |

| Gemma 3 27B | 0.4554 |

| Ministral 3 8B Reason 2512 | 0.4499 |

| Olmo 3.1 32B Instruct | 0.4381 |

| Granite 4.0-H Small | 0.4335 |

| Gemma 3 12B | 0.4289 |

| Ministral 3 3B Instruct 2512 | 0.4135 |

| Olmo 3 7B Think | 0.4022 |

| Llama 3.1 8B Instruct | 0.4011 |

| Ministral 3 3B Reason 2512 | 0.3608 |

| MedGemma 4B | 0.3564 |

| Olmo 3 7B Instruct | 0.3423 |

| SmolLM3 3B | 0.3358 |

| Granite 4.0-H Tiny | 0.3308 |

| Gemma 3 4B | 0.3194 |

| AFM 4.5B | 0.3177 |

| Model | Weighted Mean Win Rate |

|---|---|

| GPT 5.2 (medium) | 0.624 |

| GPT 5.1 (medium) | 0.5981 |

| Qwen3 235B-A22B Thinking 2507 | 0.5873 |

| gpt-oss-120b (high) | 0.563 |

| Baichuan M2 | 0.5152 |

| Qwen3 Next 80B-A3B Thinking 2507 | 0.5076 |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 0.4737 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 | 0.4697 |

| gpt-oss 20b (high) | 0.4415 |

| Qwen3 8B (Thinking) | 0.3975 |

| Llama 3.3 70B Instruct | 0.3224 |

Why build this evaluation suite?

There are already several evaluation suites for medical LLMs. A few of the most notable include:

- MultiMedQA - introduced by Google in the Med-PaLM paper

back in 2022 and rapidly adopted by the medical LLM research community. However, after just a couple of years, it has mostly saturated. This is because it mainly comprises question answering tasks that test for medical knowledge recall (e.g., medical licensing exams), which current LLMs are quite good at. These simple tasks do not accurately represent the capabilities surrounding most medical use-cases. - MedHELM - introduced by Stanford

, this is a large collection of benchmarks focused on representing real-world medical use-cases. However, only 13 of the 35 datasets are publicly accessible, preventing full replication by the community. Additionally, this means the leaderboard can only be extended to new models by the Stanford team (the leaderboard has not been updated since April 2025). - HealthBench - introduced by OpenAI earlier this year

, with questions and rubrics designed by clinicians, it is being used by frontier labs to measure “capabilities of AI systems for health.” While it is a very valuable benchmark, it solely focuses on medical conversations, so non-conversational medical capabilities are not evaluated.

We believe there is a need for a completely open and easy-to-run medical LLM benchmark, evaluated on clinically relevant tasks and updated regularly with new models. This is the goal of our benchmark suite.

Our benchmark suite currently includes 20 benchmarks that span question answering, information extraction, consumer health questions, logical reasoning questions, EHR interactions, medical calculations, and more. While most datasets are still multiple-choice question answering, the benchmarks we select have a broad range of difficulties. Additionally, we have added a few open-ended and agentic tasks, with plans to expand this further very soon (see "Future" section).

We focus in this initial version on benchmarking with open datasets to promote accessibility and reproducibility while acknowledging that many practical use-cases are still not sufficiently covered by public datasets and hence require private evaluations.

Results

Comprehensive dataset-specific scores per LLM across Medmarks-Verifiable and Medmarks-OE subsets are presented below. We dive into various interpretations of these results in the subsequent subsections. To briefly summarize these interpretations:

How difficult are the benchmarks? Benchmarks span the full range of difficulty from very easy (MedConceptsQA-Easy

How does model performance change with model size? Bigger models are typically better.

Do medical-specific LLMs outperform their general-purpose counterparts? Yes, at least for MedGemma/Gemma.

Which models are more cost-efficient and token-efficient? Open-weight LLMs were more inefficient than frontier reasoning models like GPT-5.2 (medium), which were both accurate and used low numbers of tokens. Grok-4 was an extremely expensive outlier.

Does reasoning post-training improve model performance? Yes, for most datasets except for the curious case of Ministral.

Do models overthink when they fail? Yes, although this is confounded by question difficulty.

Does increased reasoning effort improve performance? Yes, except for the PubMedQA and Med-HALT-NOTA datasets.

Does quantization affect model performance? For well quantized medium-sized models, not really.

Is there order bias for multiple choice tasks? Yes, particularly for smaller models.

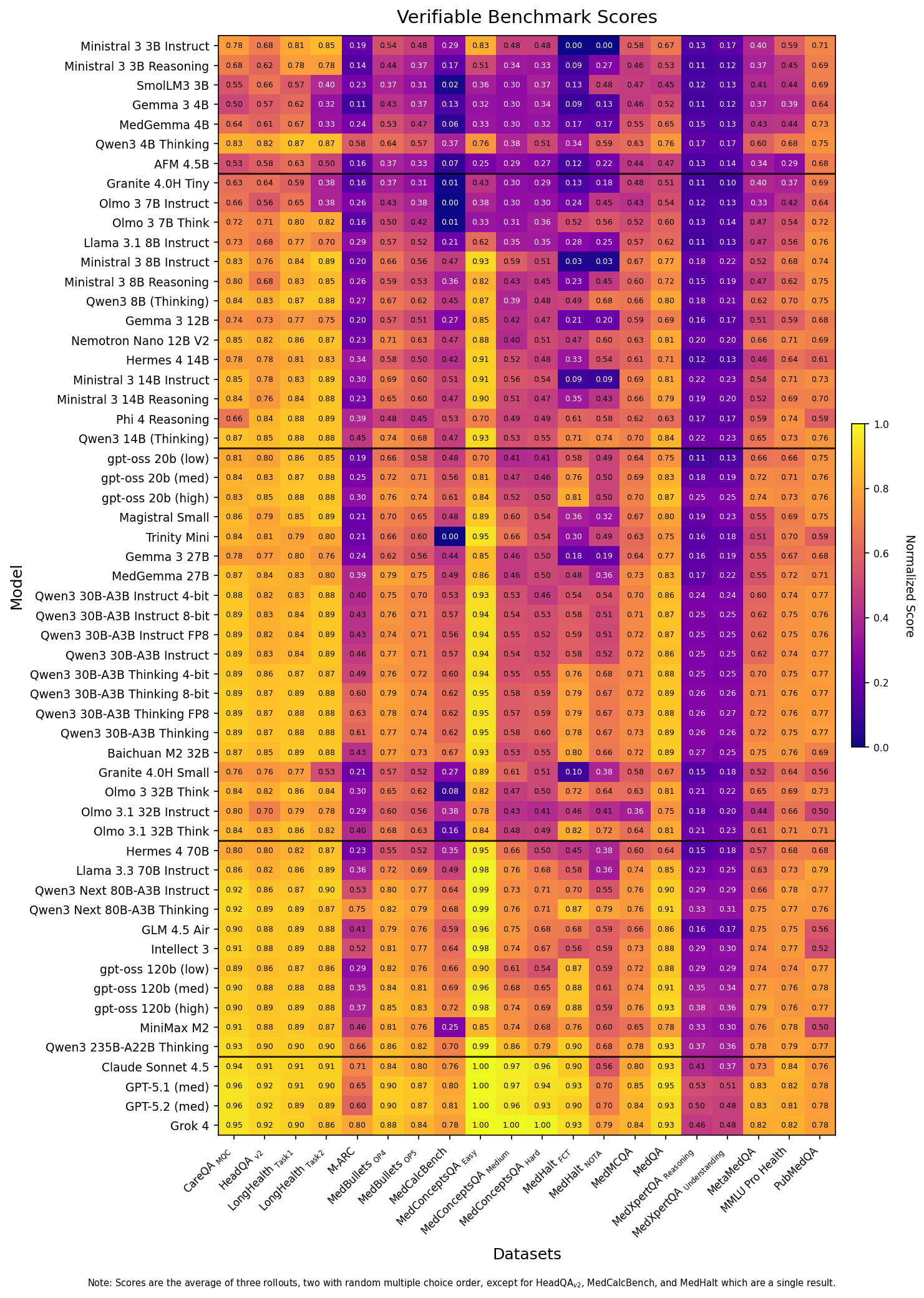

Medmarks-Verifiable Results

We evaluated 46 models on 14 different verifiable benchmarks. This includes multiple choice question answering tasks like MedQA

Figure 1: Heatmap table of the raw scores for each model across the 14 benchmarks of the Medmarks-Verifiable subset. Dark purple highlights low performance, bright yellow highlights high performance. Metrics are dependent on the benchmark.

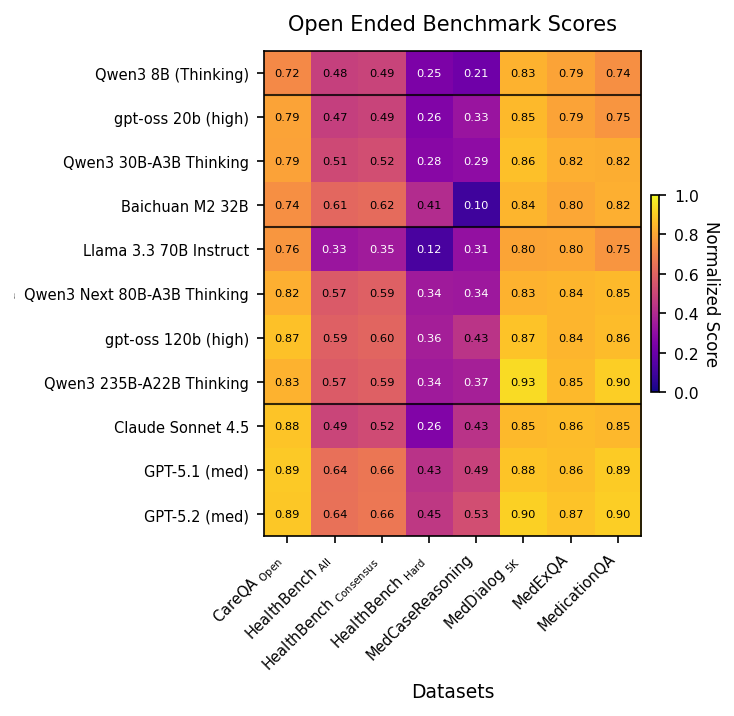

Medmarks-OE Results

Due to both time and cost constraints, we take a subset of the best performing models on Medmarks-Verifiable and report their scores on the Medmarks-OE leaderboard. These are benchmarks where there isn’t a clear exact answer, like evaluating LLM responses to patient questions. We evaluate models using an LLM-as-a-Judge approach, where a judge LLM grades the response of the evaluated LLM. We chose 12 models across four size categories.

With the exception of MedCaseReasoning

Figure 2: Heatmap table of the raw scores for each model across 6 benchmarks of the Medmarks-OE subset. Dark purple highlights low performance, bright yellow highlights high performance. Metrics are dependent per benchmark. Dark purple highlights low performance, bright yellow highlights high performance. Metric is a normalized LLM Judge score.

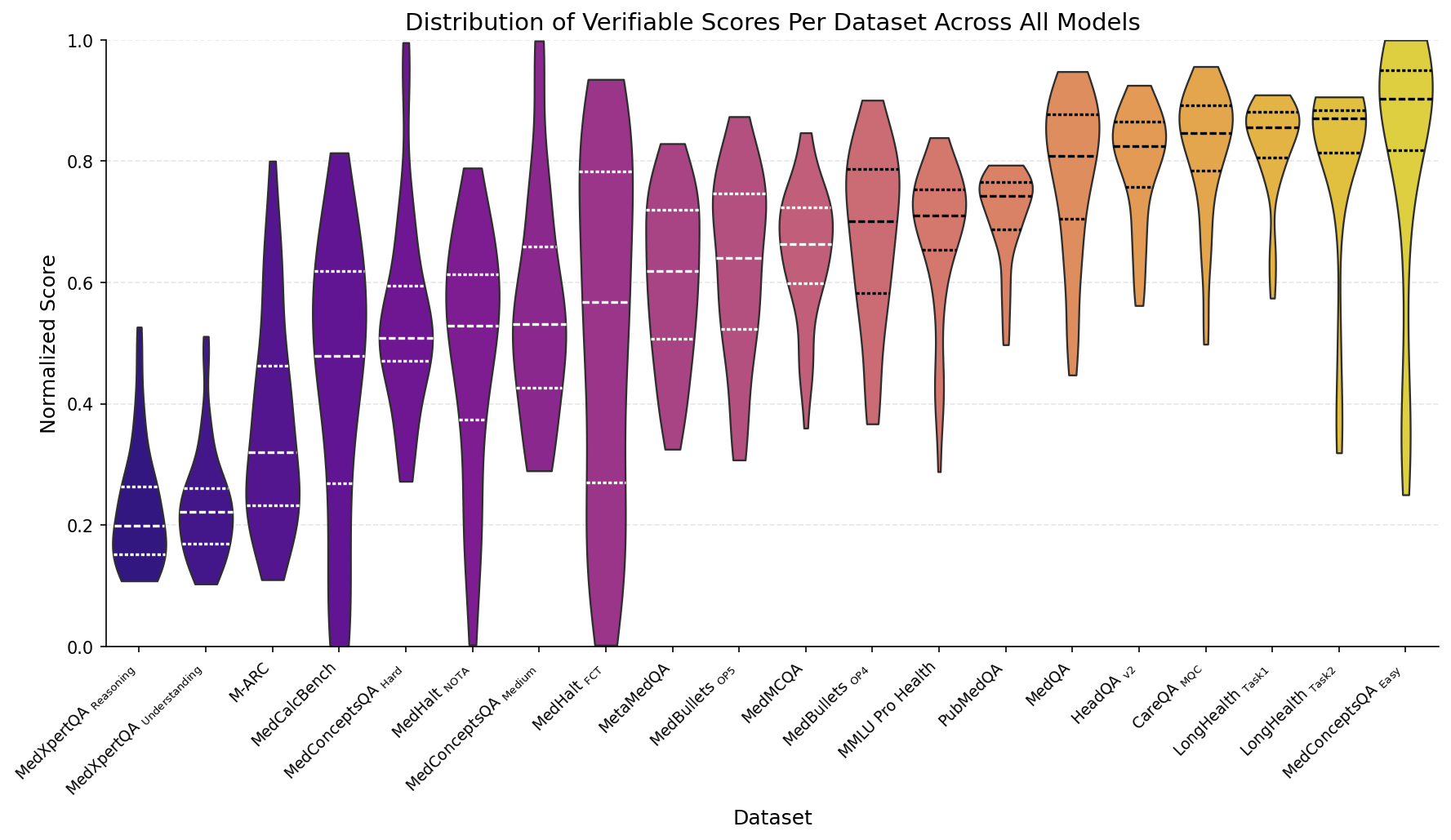

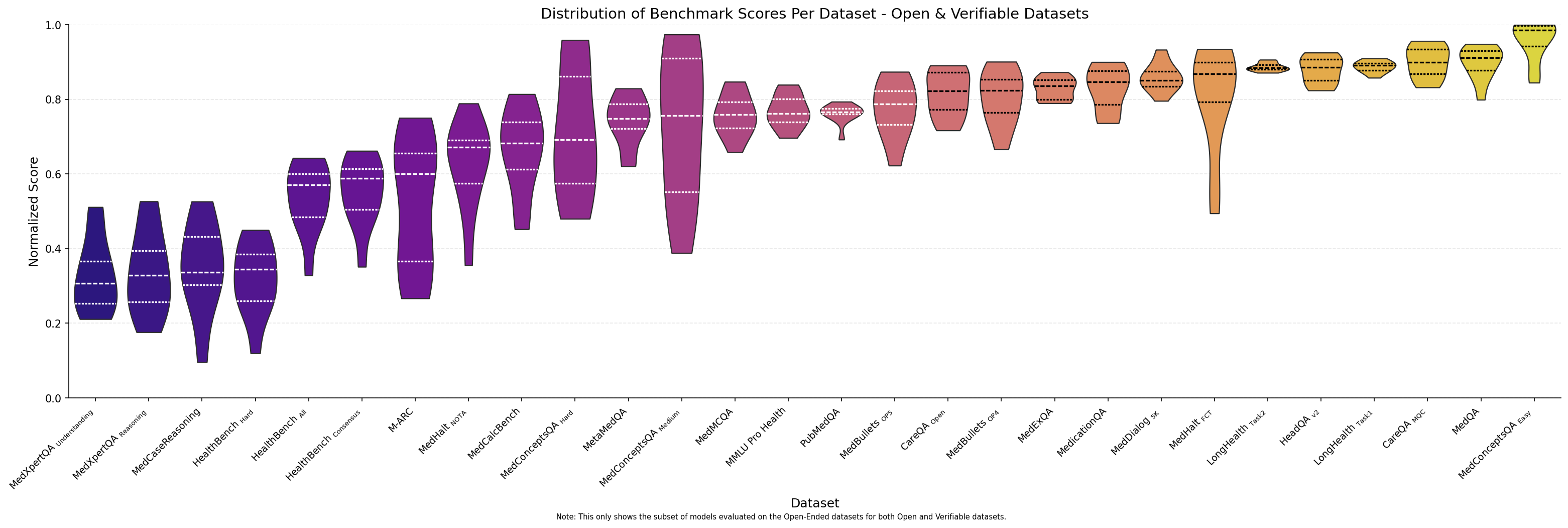

How difficult are the benchmarks?

It’s important that our benchmarks not be too easy or too hard. We observe that our Medmarks-Verifiable benchmarks span a broad range of difficulties:

Figure 3: Distribution of normalized model performance for each of the datasets in the Medmarks-Verifiable subset, across all 46 models tested.

The simplest benchmarks are ones associated with the LongHealth dataset

The most challenging benchmarks in the Verifiable subset are the MedXpertQA

Turning our attention to Medmarks-OE (which we plot with the Medmarks-Verifiable dataset for the 12 models evaluate), we see a range of difficulty in the benchmarks, with MedCaseReasoning

Figure 4: Distribution of normalized model performance for each of the datasets in both the Medmarks-Verifiable and Medmarks-OE subset across the 12 models that were evaluated on both subsets.

The performance gap from easiest to hardest datasets reveals a clear difficulty gradient, suggesting models excel at simpler long-context tasks but struggle substantially with specialized medical reasoning and understanding required for expert-level clinical performance.

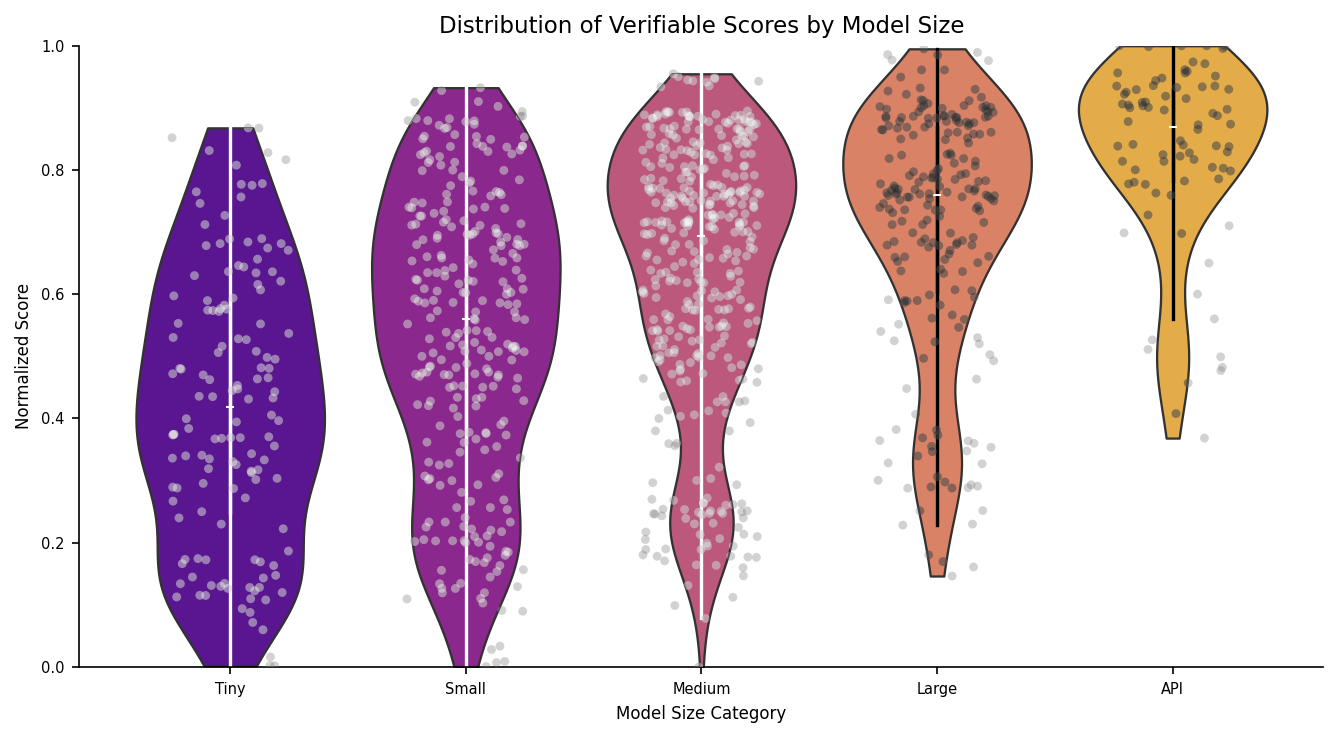

How does model performance change with model size?

To explore results by model size, we divided all our evaluated models into five weight classes:

- Tiny: models below 7B parameters. These models could be run on a high-end phone.

- Small: models between 7B and 19B parameters. These models can be run on a single consumer GPU.

- Medium: models between 20B and 40B parameters. These models can be run on a single GPU (consumer or server).

- Large: models larger than 40B parameters which can be run on one 80GB H100 node. This is the widest class as it spans two GPU models to eight GPU models.

- API: proprietary models or models requiring more than one 80GB node to run.

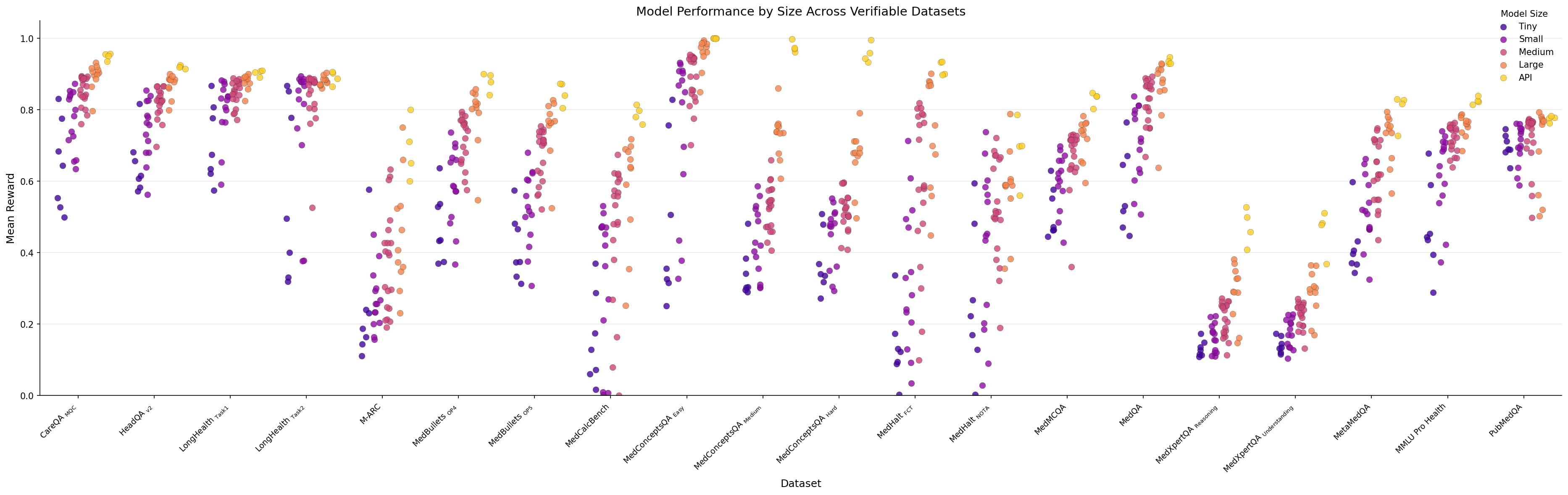

When we plot dataset performance by model size a clear pattern emerges: larger models almost always outperform smaller ones across all benchmarks.

Figure 5: Distribution of model scores based on model category for the Medmarks-Verifiable subset.

On the simplest tasks like LongHealth Task 1 and LongHealth Task 2

Conversely, on the hardest datasets like MedXpertQA

Figure 6: Scatter plot of model scores on each of the Medmarks-Verifiable benchmarks, labeled by model size.

The performance advantage of larger models is most pronounced on moderate-to-difficult datasets. For example, on MedConceptsQA Easy, the gap reaches 0.631 (large=0.968 vs. tiny=0.337), while on the hardest MedXpertQA tasks, the gap narrows to just 0.16. This suggests model size matters significantly for tasks within the capability range of current models, but provides diminishing returns on extremely difficult specialized medical reasoning tasks.

As the two tables below show, there are some exceptions to this trend. Qwen3 reasoning models consistently punch above their weight class, with 4B outperforming the mean Small model, 14B outperforming the mean Medium model, and 30B-A3B outperforming the mean Large model.

| Model | Size | Win Rate | Next size | Larger-size Avg Win Rate | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen3 4B Thinking 2507 | Tiny | 48.8% | Small | 44.7% | +4.1 |

| Qwen3 14B (Thinking) | Small | 54.6% | Medium | 51.6% | +3.0 |

| Qwen3 30B-A3B Thinking 2507 | Medium | 57.0% | Large | 56.7% | +0.4 |

And there are models, like IBM’s Granite 4.0, Olmo 3

| Model | Size | Win Rate | Prev size | Prev-size Avg Win Rate | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hermes 4 70B | Large | 47.0% | Medium | 51.6% | -4.6pp |

| Granite 4.0H Tiny | Small | 33.1% | Tiny | 37.0% | -3.9pp |

| Olmo 3 7B Instruct | Small | 34.2% | Tiny | 37.0% | -2.8pp |

| Granite 4.0H Small | Medium | 43.4% | Small | 44.7% | -1.4pp |

| Olmo 3.1 32B Instruct | Medium | 43.8% | Small | 44.7% | -0.9pp |

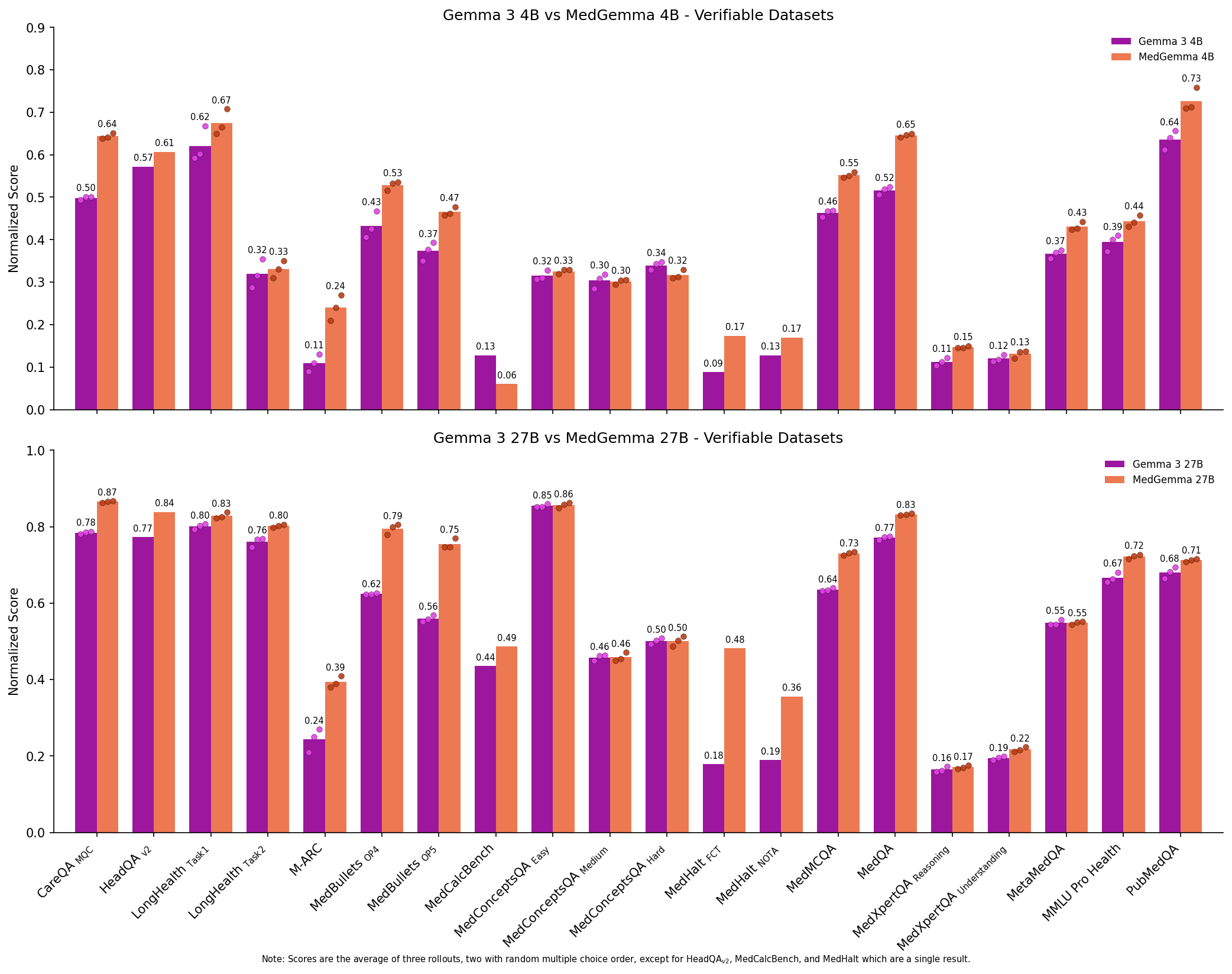

Do medical-specific LLMs perform better than their general-purpose counterparts?

It is commonly debated whether general purpose LLMs are sufficient or if we need to specifically train domain-specific LLMs for the medical domain. We evaluated three recent medical LLMs: Baichuan-M2

Figure 7: Comparing the performance of Gemma 3 models to MedGemma 3 models on Medmarks-Verifiable tasks.

We note a significant boost in mean win rate from both Gemma 3 4B to MedGemma 4B (0.3194 to 0.3564) and Gemma 3 27B to MedGemma 27B (0.4554 to 0.5069). This increase is not limited to the average, but is a Pareto improvement across all but one benchmarked health datasets, providing strong evidence that adapting models to the medical domain can be quite useful. However, modern generalist LLMs such as Qwen3 30B-A3B

Which models are more cost-efficient and token-efficient?

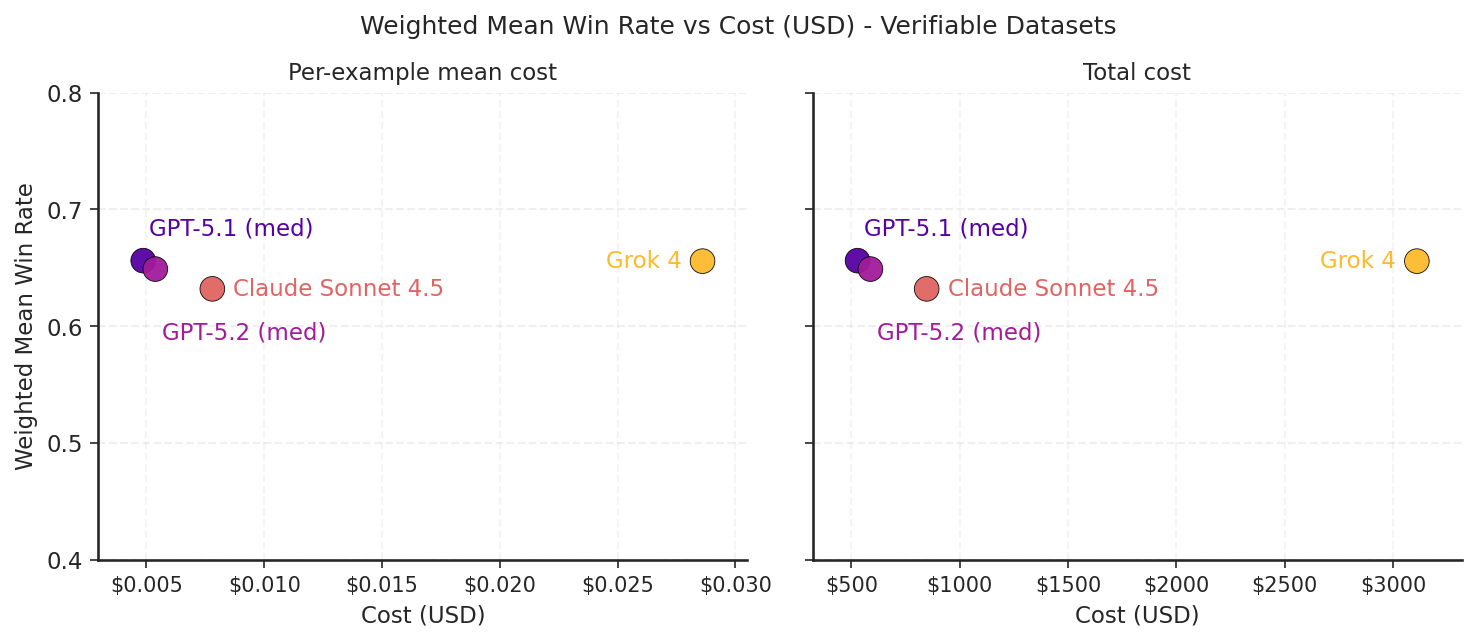

We measured average inference cost per example and the total inference cost on Medmarks-Verifiable for various proprietary models.

Figure 8: A scatter plot of the weighted mean win rate on Medmarks-Verifiable by cost for the model APIs evaluated. Cost is reported in two ways, per-example mean cost and total cost.

Of the four model APIs evaluated, Grok-4 stands out in its expense. It costs an order of magnitude more per query for medium level frontier performance on our verifiable medical benchmarks. As shown in the figure below, this is mainly due to Grok brute forcing answers with a large reasoning token spend. On the other hand, GPT-5.1 is the cheapest while also being the most performant.

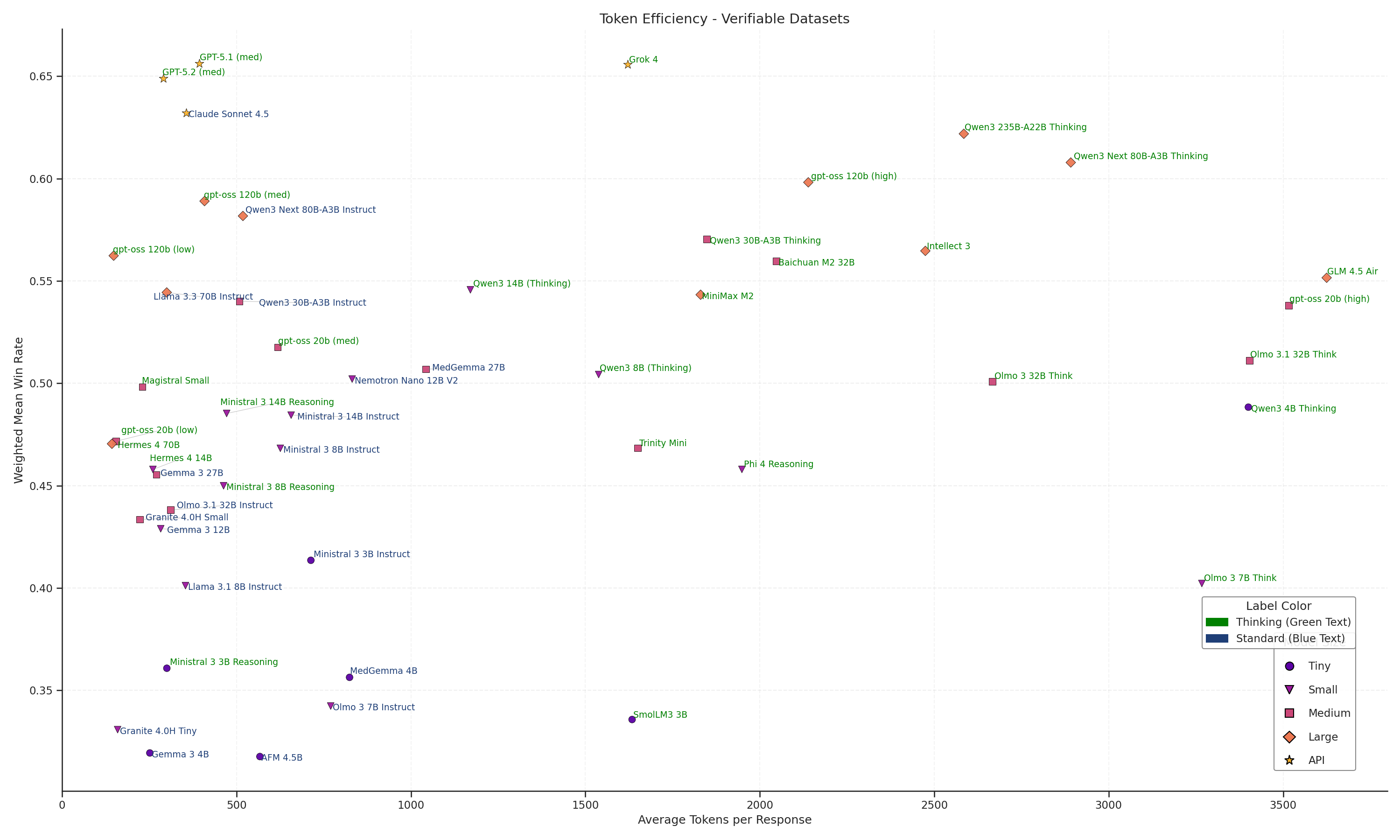

We also recorded the token use of all 46 models on our verifiable datasets. The results reveal a massive optimization gap across thinking models.

Figure 9: Scatter plot of weighted mean win rate on Medmarks-Verifiable by average tokens per response for each model. Each model is labeled by model size and if it's a thinking model or standard model.

The Pareto frontier is dominated by frontier reasoning models like GPT-5.2 and Claude Sonnet 4.5 (Green), which achieve high average accuracies (>0.7) while keeping costs remarkably low (<700 tokens). However, as we move to large open-weight alternatives, this efficiency collapses. Qwen3 235B-A22B Thinking matches the accuracy of Sonnet 4.5 but demands nearly 5x to 6x the token volume (~3,500+) to do so. It is even significantly less efficient than gpt-oss-120b (high), another open model which achieves similar results for half the cost (~1,500 tokens). This bifurcation indicates that while open architectures have closed in on performance of frontier reasoning models on medical datasets, they have not yet solved the computational cost of the chain-of-thought process.

Does reasoning post-training improve model performance?

OpenAI’s o1 model and DeepSeek’s R1 model heralded the rise of reasoning models, or thinking models, in both proprietary and open source settings, respectively. Unlike instruct models, reasoning models have an “internal monologue” before outputting their final answer. These reasoning or thinking traces allow the models to explore solutions without the same level of polish, allow a space for self-correction, and generally increase performance over traditional instruction models which directly output the final answer.

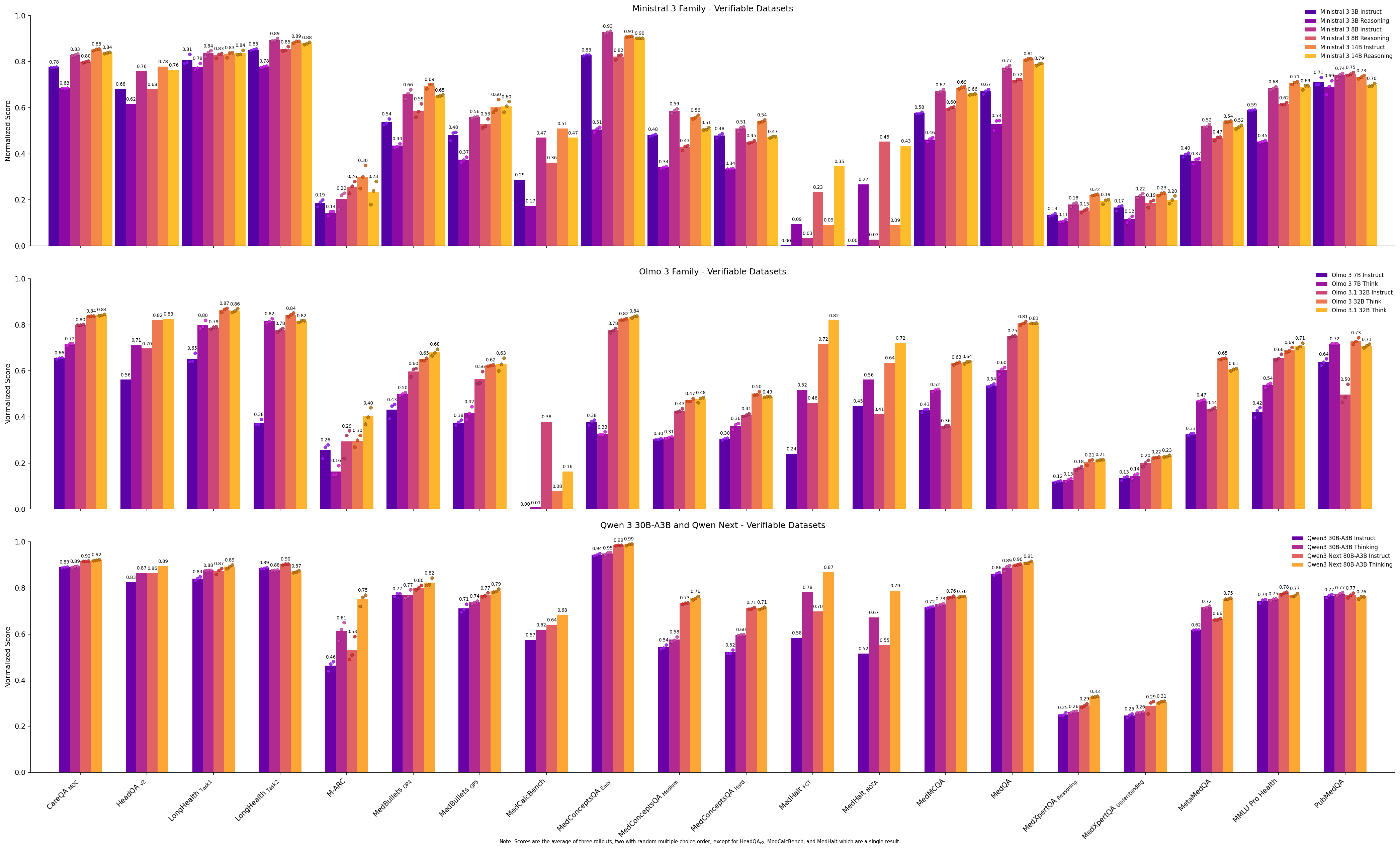

How do thinking models perform compared to their instruction-tuned counterparts? In general, post-training a base or instruct model into a reasoning model using the modern bag of tricks increases the score of the reasoning model relative to the comparable instruction model. We can see this with Olmo 3 7B, Olmo 3/3.1 32B

Figure 10: Bar plots comparing performance of instruct vs. reasoning models for Ministral 3, Olmo 3, and Qwen3 models.

Adding reasoning does not always guarantee improvement, as seen with the Ministral family of models. Here, the reasoning models underperform, sometimes significantly, compared to their instruction counterparts on almost all datasets. From our medical benchmark alone, we cannot tell if this is a case of catastrophic forgetting or overfitting, overly divergent post-training data between the instruction and reasoning models, undertrained reasoning models, an issue with verifiable rewards, or something else.

Do models overthink when they fail?

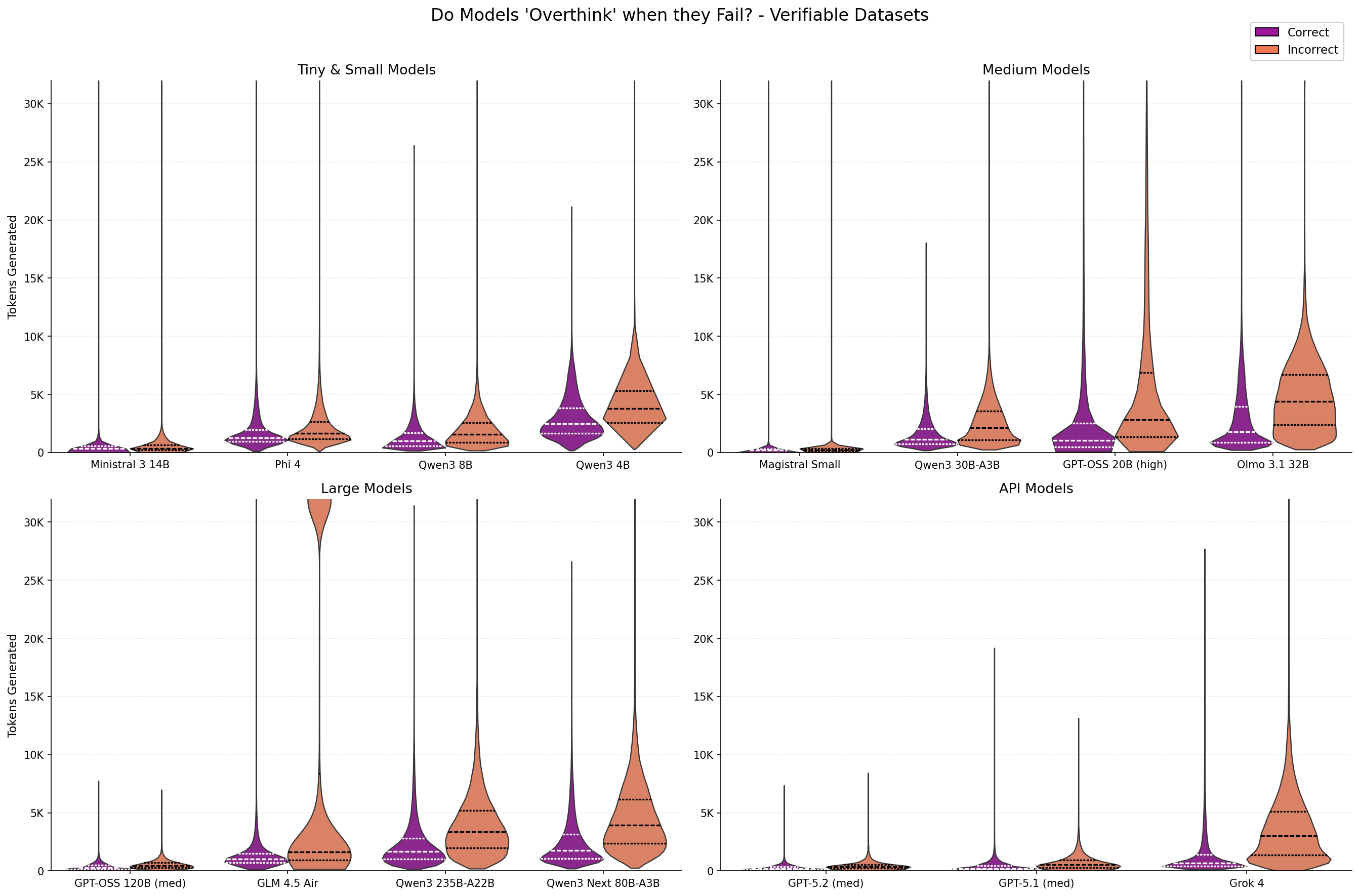

While reasoning models show improved performance, it begs the question how reasoning models behave when they get questions wrong. We select the best, worst, and two midrange models per category (excluding “duplicate model” like gpt-oss reasoning levels and Olmo 3 vs 3.1) and compare how many tokens they generated for correct and incorrect responses.

Figure 11: Distribution of number of tokens generated for different models when the response is correct or incorrect.

The above figure highlights a subset of reasoning models to show the trend that more tokens are typically generated for questions that are answered incorrectly. This trend holds across model size and model providers. GLM-4.5 Air is a particularly interesting outlier where a large proportion of the responses with incorrect outputs had very long generations. :

Comparing across models with different pretraining and posttraining datasets and strategies adds confounding factors which complicate this analysis. Fortunately, OpenAI’s gpt-oss models allow us to directly compare thinking budgets on downstream performance in a more comparable setting.

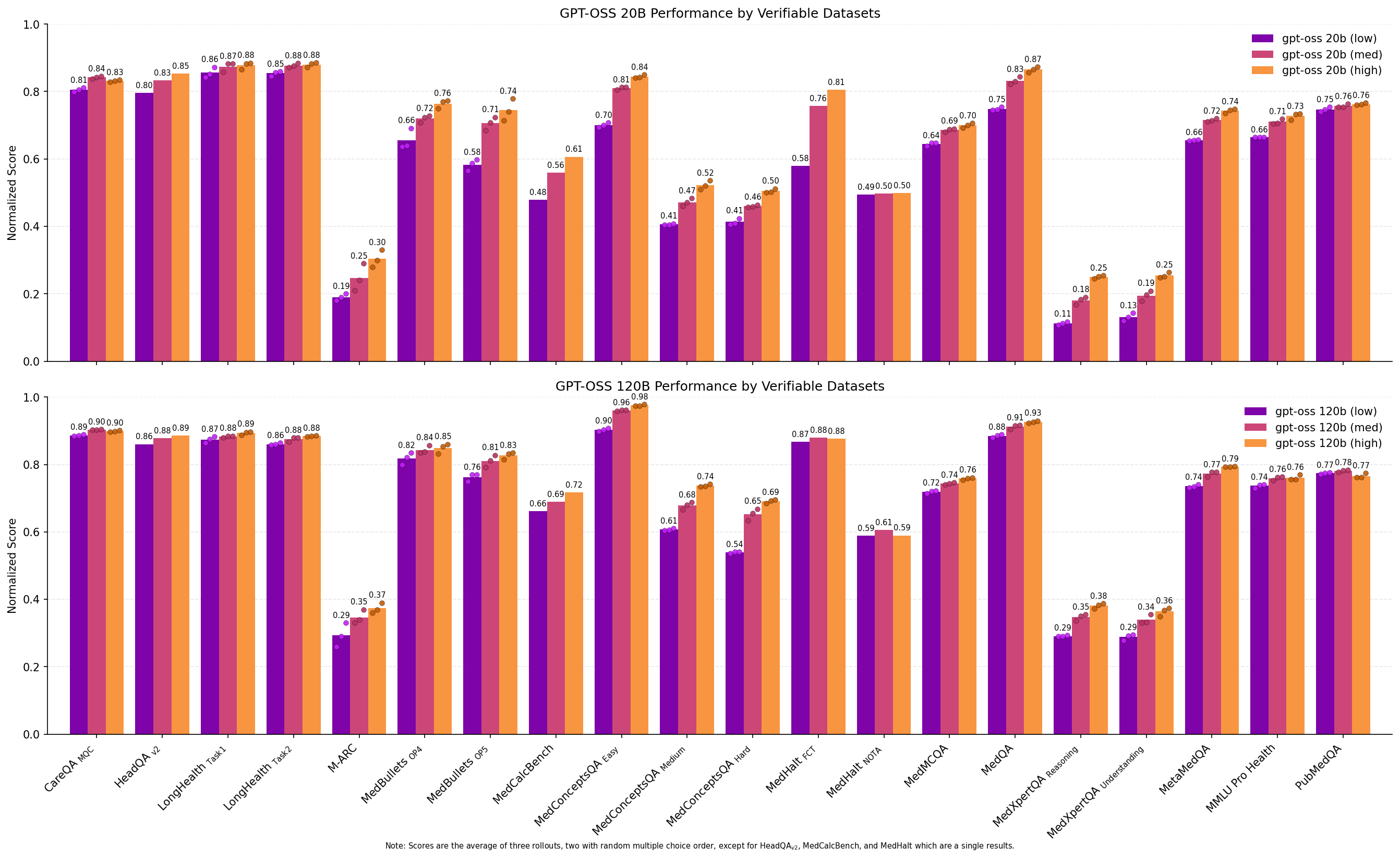

Does increased reasoning effort improve performance?

OpenAI’s gpt-oss models 20B (with 4B active parameters) and 120B (with 5B active parameters) support setting reasoning effort between low, medium (the default), and high, with higher reasoning effort tending to produce more reasoning tokens before the final answer. This allows us to directly test in a controlled setting the effect of more reasoning tokens on downstream health performance.

Figure 12: Bar plots comparing performance of different reasoning levels for gpt-oss models on the Medmarks-Verifiable benchmarks.

The results are clear: while gpt-oss 20b (medium) and gpt-oss 120b (medium) are well-performing models in their own right, increasing the reasoning token budget to high produces stronger results. gpt-oss 120b (high) is the third strongest model on our local benchmark suite, outperforming three similar sized or larger models with more active parameters: GLM-4.5 Air (106B-A12B)

From the per dataset results, we can see that increasing the reasoning level results in an almost Pareto improvement on scores across datasets except PubMedQA

Figure 13: Distribution of number of tokens generated for gpt-oss models under different reasoning levels when the response is correct or incorrect.

As discussed in the previous section, we also see that gpt-oss-20B and 120B exhibit the “overthinking” problem where models spend more tokens to reason on questions they eventually get incorrect. However, given that increasing reasoning tokens increases performance overall, it’s incorrect to conclude that increased thinking leads to more incorrect answers. Rather it would appear that harder questions, or questions the model doesn’t know the answer to, lead to more reasoning in an attempt to figure out the correct answer.

Does quantization affect model performance?

Often, models are quantized to save memory and increase inference speed. However, depending on the quantization method, this can degrade model performance. Here we study this in the context of our medical benchmarks, focusing on Qwen3 30B-A3B Instruct and Thinking as examples. We ran both the official BF16 precision and FP8 quantized weights and community-quantized AWQ 8-bit and 4-bit versions.

Figure 14: Bar plots comparing performance of quantization levels for Qwen3 models on the Medmarks-Verifiable benchmarks.

Our results show minimal performance degradation from quantization on most datasets, with the more aggressively quantized AWQ 4-bit model suffering a small but consistent penalty on most datasets.

Our results align with Zheng et al.

Is there order bias for multiple choice tasks?

Prompt format can significantly affect the performance of foundation models. A recent paper

We chose to run three rollouts of almost all our multiple choice benchmarks. The first rollout was dataset order and the second two rollouts involved randomly shuffling answer order to test if modern language models are biased from answer choice position.

Each multiple choice dataset’s variance, the difference between the maximum and minimum score, is plotted below. While the effects are not evenly distributed across datasets, we can draw two conclusions from this chart:

- Modern language models can still be tripped up by multiple choice question order, even frontier models. For example, Grok 4 exhibits high scoring variance when shuffling the answer order in M-ARC.

Because M-ARC is a small dataset, we spot-checked variance by running additional rollouts with the same answer order for all three frontier models. In this setting, Grok 4’s variance decreased from 0.11 to 0.02. In contrast, GPT-5.1 (medium)’s variance decreased from 0.05 to 0.03 and Sonnet-4.5 from 0.05 to 0.02. This suggests that in Grok 4’s case, multiple choice answer reordering has a larger effect than model sampling randomness. - Smaller models tend to suffer more from choice order effects than larger models.

Figure 15: Variance of model performance across all Medmarks-Verifiable benchmarks. Dark purple highlights low variance, bright yellow highlights high variance. Given we typically evaluate a model three times on each benchmark, we report the maximum score subtracted by the minimum score for a given benchmark. Note that since we only performed a single evaluation for HeadQA-v2

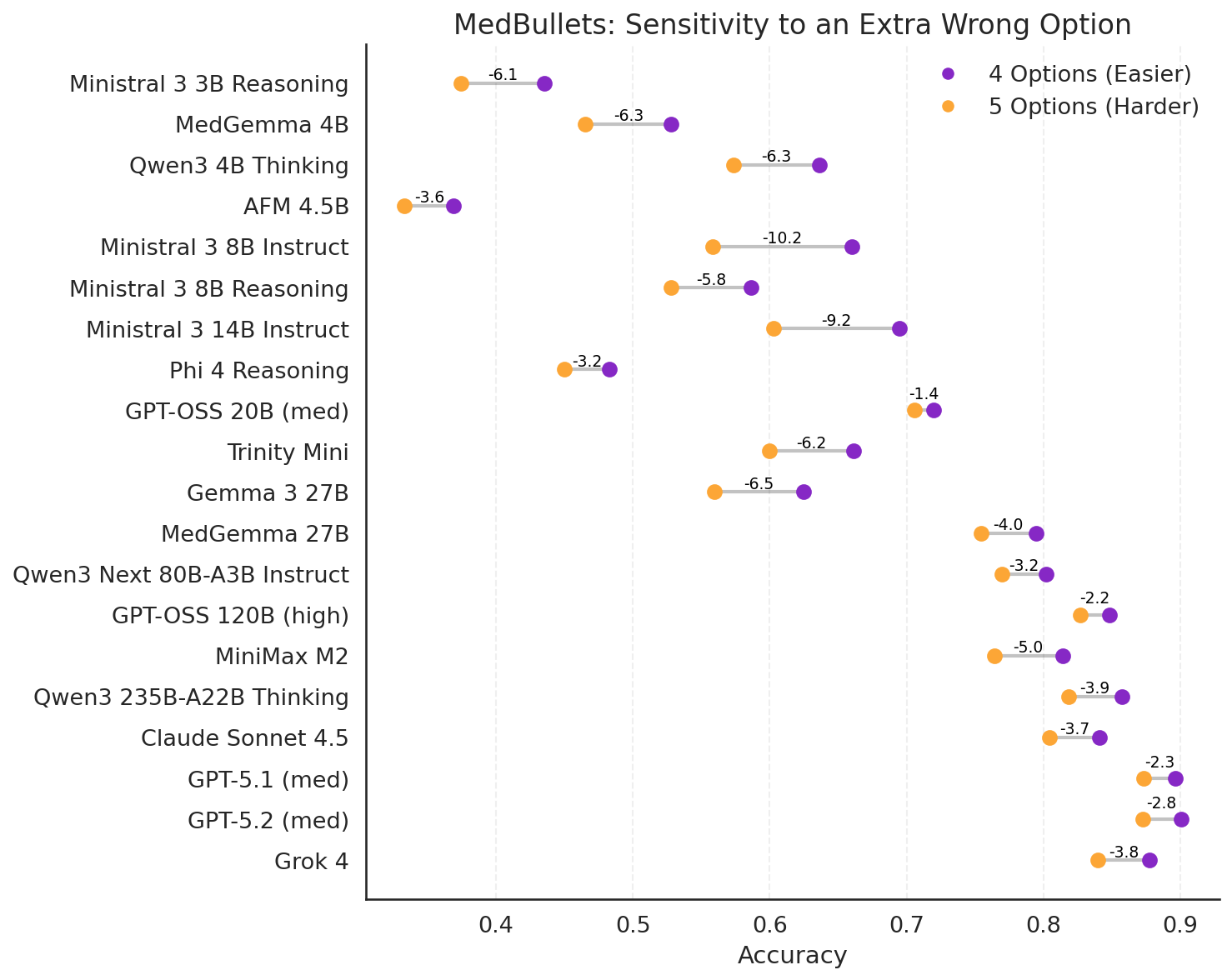

MedBullets

Figure 16: Comparing model performance with and without an extra option on the Medbullets benchmark.

Plotting the average accuracy across all rollouts, we can see that the combination of adding an additional answer along with random shuffling of the answer orders can result in a large negative reduction in performance. This “distractability” is greater for smaller models and/or models which are not as confident in their answers. As one would expect, larger models appear to be less distractible than smaller models.

Medmarks doubles as reinforcement learning environments

At Sophont, we are working to develop LLMs with improved medical understanding and reasoning abilities. Since we implemented the datasets in the verifiers framework

Benchmark Construction

Medmarks is built on Prime Intellect’s verifiers library

We currently implement a total of 20 datasets which fit this criteria (eight of which have training splits in addition to the evaluation split).

Prompt selection is an important part of dataset evaluation, with entire libraries dedicated to prompt optimization (e.g., DSPy

All language models were evaluated using their officially recommended sampling parameters, e.g. temperature, top_k, min_p, etc. Where model creators did not specify sampling parameters, we elected to use community settings or common defaults. LLM as a Judge models use either their default sampling arguments, falling back to OpenAI’s HealthBench

A major caveat: for a few datasets we made a few changes to save time and cost of evaluation:

- MedConceptsQA

and MedDialog have 819K and 25k examples, respectively, so we only evaluate on a subset of these datasets. MedConceptsQA tests the model’s knowledge of ICD-10 codes, which have a hierarchical structure corresponding to different categories. We used this structure to select a representative sample of 2,000 questions from the easy, medium, and hard subsets for a total of 6,000 questions. Details of this selection process can be found in the data appendix. For MedDialog, we selected the first 5k examples out of 25K instead. - We only perform one run of HeadQA-v2

, MedCalc-Bench , and Med-HALT instead of three.

Multiple-Choice Datasets

At first glance, grading the results from a multiple-choice benchmark appears easy: either the model returns the correct answer or not. However, in practice, when one wants the same environment to be usable for RL training and thus accept variable outputs, the task of grading multiple choice answers without resorting to a LLM-as-a-Judge becomes a bit tricky.

During spot checking, we noticed models would be given an incorrect grade but had chosen the correct answer, just not in the environment’s intended format. Smaller models have a greater tendency to ignore formatting instructions and give unexpected but correct answers, but even GPT-5.1 would sometimes write a paragraph despite being prompted for a concise answer format. To resolve this, we constructed a multiple-choice grading function which accepts the multiple-choice letter (or number), the exact answer text, or the letter with the exact answer text. This function also strips dangling thinking traces, normalizes capitalization, punctuation, and whitespace, accepts optional answer prefixes to look for the answer, and attempts to account for negation.

In detail, the grading function normalizes and strips known extraneous text, looks for an exact match answer (only the multiple choice character), looks for the answer character leading the answer text, attempts to match the answer near common answer prefixes (“the answer is:”, “in conclusion”, “best supported”), attempts to find the answer character in the tail without any negation (“C is incorrect”, “not C”), and finally attempts to exact match the answer text if it exists in the first or last sentence without nearby negation. This strategy of handling answer outputs has a few pitfalls, like grading an answer as wrong if the correct answer is provided in the middle of a paragraph. Another known "problem" is when the wrong letter choice is followed by the correct text. This is currently graded as incorrect.

Our multiple-choice environments also support randomized answer order, controlled by a seed. Our randomization method attempts to account for anchor answers, such as “all of the above” and “A or B” and only randomizes the order of questions before or between any anchor answers.

Open Ended Datasets

Before modern language models, open ended datasets had three choices:

- using human graders which was expensive and not repeatable outside of the introductory paper

- using classical language metrics such as ROUGE-L

or n-gram overlap which tends to fail on semantically identical but different text, such as abbreviations or synonyms - using a semantic similarity score such as BERTscore

, which lacks the model language model’s world knowledge

Following Stanford’s HELM benchmark

We reused any LLM judge prompt whenever the original dataset papers defined their LLM judge prompt. If the dataset did not contain a specified prompt, we then used preexisting LLM judge prompts, such as those found in Stanford’s HELM benchmark, with light editing when needed. If there was no pre-existing LLM-as-a-Judge prompt, we created our own judge prompts informed by No Free Labels paper

Creating a new benchmark meant we could also upgrade LLM-as-a-Judge models to the latest high performing small and medium models. We considered Claude Haiku 4.5, Gemini 2.5 Flash, Grok 4 Fast, GPT-4.1 mini, GPT-4.1 nano, GPT-4o mini, GPT-5 mini, and GPT-5 nano. We selected our judge models in a three-step process. First, we sampled a subset of questions and answers from a representative set of datasets. We used LiteLLM Proxy to cache a local model’s answers and scored three identical rollouts per question with each judge. Second, we created a custom web app to crowdsource blind head-to-head judge comparisons on questions with the most disagreement between them to rank potential judges. Third, these crowdsourced votes were then compared with judge consistency across all three rollouts. Higher ranked judges with low variance were preferred over judges with high variance across rollouts. When two judges were graded similarly, we chose the less expensive option.

For this initial iteration of the Medmarks benchmark, we chose to use one judge model: GPT-5-mini for all benchmarks except MedExQA where GPT-5-nano was widely preferred by our human graders.

In this iteration of our benchmark, we only selected a subset of models that performed well on Medmarks-Verifiable for evaluation on Medmarks-OE.

Future

We hope our benchmark suite brings us closer to real-world assessment of LLM medical capabilities in a more reproducible and accessible manner.

We will soon be adding more benchmarks to our benchmark suite:

- ACI-Bench

- MedAgentBench

- AgentClinic

- K-QA

- BioHopR

- MedRedQA

We’ll also add more models to our leaderboard. For example, many of the leading Chinese model APIs were slow, unstable, and timed and errored out frequently, leading us to omit DeepSeek R1 and v3.2 Speciale, Kimi K2 Thinking, GLM 4.6, and Qwen3 Max in this initial release. Additionally, as new models are being released we plan to add them. For example, we’ll be adding models from the Google Gemini 3 and NVIDIA Nemotron 3 families shortly.

Of course, we not only want to evaluate LLMs but improve LLMs for medical tasks. Given we now have these RL environments, we plan to use them to push the medical capabilities of open-source LLMs further.

Another future direction for us not currently covered by Medmarks is benchmarking of vision-language or other multimodal medical capabilities. Medicine is inherently a very multimodal domain, but we believe it’s important to first properly evaluate and understand performance in the narrow text domain before moving onto full multimodal evaluation.

Once again it is worth highlighting the limitations of our approach here. The current version of the benchmark is heavily biased towards single-turn question answering tasks, although it does include the open-ended subset, and broader multi-turn medical benchmarks are soon to come. There are also very little end-to-end clinical workflows being evaluated in these benchmarks. Additionally, there is limited evaluation of fairness/bias and safety. These are all components we’d like to touch on in future versions of this benchmark suite, including building new benchmarks from scratch, and we’d love feedback and ideas!

Therefore, if you’re:

- a researcher who has suggestions for additional benchmarks

- a clinician open to providing feedback and brainstorming new approaches for benchmarking

- a model provider and want us to add your model to our leaderboard

please contact us at [email protected] or message us on Discord.

Finally, we are hiring! If you are interested in training and evaluating medical LLMs, please send in your resume to [email protected].